Gender Differences in the Brain--Really Not a Big Surprise, Is It?

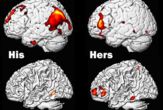

Views of the brains of men and women

Brain research that has a bottom line ought to offer insights into gender differences in teaching and learning. Consider this:

Men and women do think differently, at least where the anatomy of the brain is concerned, according to a new study.

The brain is made primarily of two different types of tissue, called gray matter and white matter. This new research reveals that men think more with their gray matter, and women think more with white. Researchers stressed that just because the two sexes think differently, this does not affect intellectual performance.

Psychology professor Richard Haier of the University of California, Irvine led the research along with colleagues from the University of New Mexico. Their findings show that in general, men have nearly 6.5 times the amount of gray matter related to general intelligence compared with women, whereas women have nearly 10 times the amount of white matter related to intelligence compared to men.

It wouldn't surprise most observant, aware people that men and women think differently, but now there's research to prove it. So far, so good, but if intellectual performance is not affected by differences in thinking then what does it matter?

The results from this study may help explain why men and women excel at different types of tasks, said co-author and neuropsychologist Rex Jung of the University of New Mexico. For example, men tend to do better with tasks requiring more localized processing, such as mathematics, Jung said, while women are better at integrating and assimilating information from distributed gray-matter regions of the brain, which aids language skills.

Wait a minute. Paraphrasing the results, the study tells us that men do better in math and women in languages. Is that what I just read? What else do I need to know?

Scientists find it very interesting that while men and women use two very different activity centers and neurological pathways, men and women perform equally well on broad measures of cognitive ability, such as intelligence tests.

Here's what I think I know and ought to keep in mind in teaching economics. First, male and female students should perform equally well in the course. However, when math is involved, female students will not perform as well as males. When language is involved the males will have more difficulties.

The question remains is there anything a conscientious instructor can do about these research findings to help the females get through the math in an economics class and help the males deal with the fine points of language. Until the answer is provided, perhaps by additional research, the best an economics instructor can do is try to explain concepts as clearly as possible and provide an array of learning opportunities that engage the white matter brain cells and the gray matter brain cells.